Home » Macro Investing

Category Archives: Macro Investing

Brinkmanship Provided Opportunities in T-Bills

Last week, just prior to the temporary resolution of the debt ceiling issue, I wrote up this article for Seeking Alpha. It covered two topics. The first was about a couple of articles discussing price action in the Bill markets. The second and more interesting part illustrated how investor preferences were creating arbitrage opportunities for T-Bill investors. Let me know what you think.

We Interrupt Our Regularly Scheduled Programming

I was doing my morning reading prior to the release of NFP, and came across this article from Bloomberg. The article is about Takeshi Fujimaki. In addition to being a “former adviser” to George Soros, he won a seat in Japan’s upper house of parliament last month. He calls the JGB market a bubble which has been said before but the very last paragraph blew me away:

“It’s impossible to avoid a default at this point, but what’s important is to create a system to avoid the same mistake and that’s where I can contribute as a politician,” Fujimaki said.

By the way, I found the above paragraph even more staggering than the one before it. In the paragraph before, Fujimaki said that “The yen’s fundamentals suggest to me it should be around 180 to 200 per dollar.”

Wow. We have all read (and re-read) Kyle Bass on how Japan is about to implode (I’ll add that I am a fan of Bass). There is a massive difference, however, between a hedge fund manager suggesting JGB’s collapse and an elected politician (even if ex-hedge fund) comes out and tells the world that a JGB default is inevitable.

A Fed Primer: Mechanics of QE, Money Multipliers and Inflation

“The good God is in the detail.” – Flaubert

This piece began as an effort to understand Fed money creation and to be able to effectively answer why the Fed can’t simply hand over its US government bond portfolio to Treasury. My fundamental assumption was that it was necessary and useful to understand the mechanics. Rather than “the devil being in the details,” I found that quote from Flaubert more appropriate. I find the idea fitting that by appropriately understanding the details, one can create an appreciation of the whole. This piece covers the necessary working details of the Fed and money. This piece will be the first in various pieces that will use the work herein to address the Fed, market activity and intelligent speculation, including why we can’t eliminate our debt by swapping Fed holdings with Treasury liabilities.

Balance Sheets and T-Accounts

To understand how money works, consider a closed system with one bank, the Fed and the Treasury (UST). This is sufficient to both describe and understand what happens on the Fed’s balance sheet as the one bank represents the banking system in aggregate.

In the beginning, there is no Fed balance sheet, and no new UST issuance. Anything already issued exists as an asset somewhere else. The bank starts with $100 in deposits which shows up as a debit or liability because the owner of the account can come anytime to claim the $100. As the bank has not yet done anything with the deposit, the $100 is an asset on the balance sheet of the bank. It would, of course, look to put this money to work via the purchase of an asset, e.g., making a loan or buying UST notes. Here is what it looks like. In aggregate, there is no money growth and this can be seen as the Net economy wide is in balance: credits = debits.

Time 0 (Pre-Fed balance sheet operations):

|

Bank |

Fed |

UST |

Net (Economy) |

||||

|

Cr |

Db |

Cr |

Db |

Cr |

Db |

Cr |

Db |

| $100Cash | $100Deposit | $100 | $100 | ||||

Next, the UST needs to issue new debt, conveniently in the amount of $100 and sells that note to the bank. The $100 cash is transferred to the UST from the bank. The UST has created a liability to the Bank, so the $100 Note shows up as a debit for the UST and a credit for the Bank. While there are more entries for the individual entities, the net balance for the economy is still zero since the sum of credits and debits are equal.

Time 1 (UST issues debt):

|

Bank |

Fed |

UST |

Net (Economy) |

||||

|

Cr |

Db |

Cr |

Db |

Cr |

Db |

Cr |

Db |

| $100Note | $100Deposit | $100Cash | $100Note | $100 | $100 | ||

| $100 | $100 | ||||||

Once the Fed decides to purchase securities for its own account, it creates the money. Everything must still be in balance. The Fed simply arranges for a credit balance matching the price of the note to show up in the account that the Bank has with the Fed. That credit balance can then be used as the Bank sees fit. At the same time, currency is a liability of the Fed and shows up as a debit in the Fed’s balance sheet. The purchase of the note shows up on the Fed’s books as $100 note.

Time 2 (Fed purchase):

|

Bank |

Fed |

UST |

Net (Economy) |

||||

|

Cr |

Db |

Cr |

Db |

Cr |

Db |

Cr |

Db |

| $100

Cash (from Fed) |

$100

Deposit |

$100

Note |

$100 Currency | $100

Cash |

$100

Note |

$100 | $100 |

| $100 | $100 | ||||||

| $100 | $100 | ||||||

The economy wide balance sheet still balances. However, it is now larger, at a size of $300. There is an extra $100 of currency in the system. The Fed created that money out of thin air when it credited the account for the Bank in exchange for the $100 worth of notes. While the numbers are different, this is the situation as it is now in the US economy: the Fed has created money.

The Money Multiplier

The money multiplier, as it works with banks and reserves, is well described in many textbooks. Briefly described, a bank need only post as reserve a fraction of the amount of deposits or liabilities that it obtains. The current ratio requirement is 10%. That is, a bank must hold as reserve $10 for every $100 of deposit liabilities (this is not quite right, see FRB here). It then may purchase assets with the other $90. This then occurs at the next bank that takes in the $90 as a loan and must hold $9 in reserve. $81 is now available at the second bank for investment. In the extreme, the money multiplier can create 1/(reserve ratio) in total money. In this case, that would be $100/10% = $1000. Keep in mind that there is a matching $1000 of liabilities. Also keep in mind that this is the most that can be produced; frictions will keep the ratio lower.

This is not the only source of money and leverage. Collateral can also be used in the same way was the multiplier. Consider an entity that buys a debt security. They can use the note as collateral to fund the asset purchase. The lender will require a haircut. That is, lenders require the loan to be over-collateralized loosely based on the liquidity and volatility of the asset. For a US Treasury note, that might be 95% of the value of the note. For a corporate bond or a stock, it might be only 50%. The rest needs to be in actual capital. It also turns out that the lender can then take the collateral and re-lend it out again to fund their loan to the original entity. They, too, will get a haircut on their collateral. And so on. This too will lead to a multiplier, albeit a lower one based on the aggregate haircut levels across collateral types. This recycling of collateral is called rehypothecation and is what is referred to as the “shadow banking sector” because it is not regulated by the Fed in the same was as deposits are.

The above paragraph describes this activity as lending but the lending is done via the repo market. That is, the transactions are buy-sell agreements rather than collateralized loans. That means that the lender actually does own the collateral for the period of the loan. That is what enables the rehypothecation. As a notable aside, trouble can occur if a party defaults on its loan somewhere in the chain. This is most especially true for collateral that requires a large haircut, such as stocks or high yield bonds. If a bank somewhere done the chain defaults, there becomes a problem as to how to disentangle multiple claims of the same collateral. A counterparty might have a loan of $200 against $400 of collateral. If its lender goes under, then the counterparty sustains a loss if the collateral is unable to be obtained or even if it simply takes too long to be useful. This is one of the biggest issues that came about when Lehman declared bankruptcy. See this IMF report for more information.

Inflation and Money

Milton Friedman said that “substantial inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” Yet there is no substantial inflation despite a large increase in the monetary base. As usual, there is something more than the sound bite. That something is the equation MV=PQ. The equation indicates that money supply (M) multiplied by the velocity (V) of money is equal to prices (P) multiplied by output (Q). A reasonable intuitive, working definition of velocity is that it represents how efficiently money is being used in the economy. Higher velocity means that each dollar is being used many times over – much like a gear increases force. Incidentally, we measure the quantity PQ as real GDP. You can find a picture of Friedman’s license plate, MV=PQ, and a similar explanation here. There is also more about Friedman’s quote here.

Friedman viewed V and Q as relatively stable. That is why he simplified his quote as M being directly proportional to P. This also makes good sense from the perspective of supply and demand. We price everything in dollars. If the amount of dollars increases relative to the amount of goods, it stands to reason that prices will go up since there are more dollars. In math terms, the price of a good could be looked at as price = (# of dollars)/(supply of good). Consider a micro-economy with money supply $10 and 100 widgets. The price of widgets should then be $10/100 or 10c. This is, of course, not a real example but just an illustration of how the dynamic works. This is one reason why the word “substantial” is so important because in the short run prices are impacted by many factors.

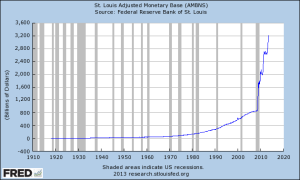

Nevertheless, the monetary base has expanded quite dramatically.

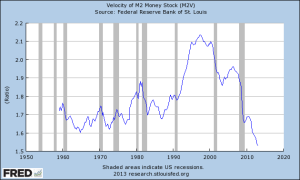

To put this in perspective, consider that the money supply has grown 370% since August 2008, just under 5 years ago. That kind of growth took nearly twenty years in the prior period (Oct 1989 to Aug 2008) and that prior period was viewed at the time to be a very high money growth period. But look at the velocity of money:

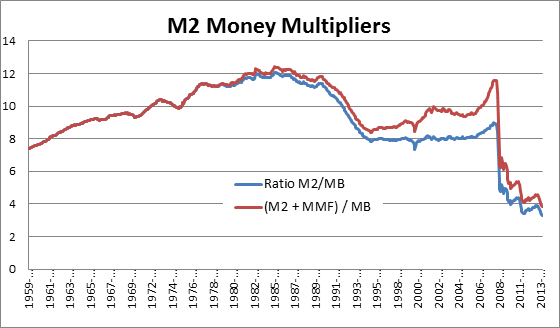

The decline is unprecedented in modern US economic history. Consider the following, as well:

The chart shows the ratio of M2 to the monetary base (MB). The blue line is simply M2 divided by the St. Louis Adjusted Monetary Base. All data here are from FRED. Deposits became less important since the 1980’s and M3 is discontinued, therefore the red line adds institutional money market fund assets to M2 before dividing by MB. It appears to provide a more continuously sensible data series. Regardless which series one prefers, it is clear that the money multiplier is broken, at least as it relates to M2 as given. M2 is not all types of money. It includes currency, checking deposits, savings deposits, retail money market funds and small time deposits. An intuitive understanding of the money multiplier, like velocity, is how efficiently the monetary base is integrated into what people actually use to buy things. The Office of Debt Management (ODM) has termed this “effective money” and that term is a good fit as a concept. A measurement is necessary in order to use the concept. At one time, M2 was considered a reasonable assessment of effective money. That is no longer the case. In this report, ODM calculates effective money as M2 + shadow money.

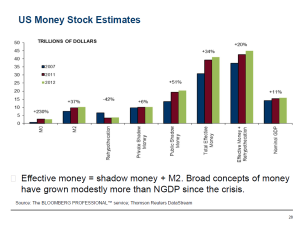

This is slide 78 of the fiscal 2013 Q2 report referenced above. It is clear that no matter which measure of money that one looks at the multiplier is broken. That is, additional money has not been multiplied at all but instead been “downshifted.” This slide shows Total Effective Money has grown 34% since 2007; effective money + rehypothecation (a broader measure that this author believes is a better measure of effective money, the concept) has grown merely 20%. This is not the type of substantial money growth that Friedman had in mind when anticipating inflation.

Either the transmission mechanism is not working properly or money is being withheld from the economy or some combination of both. There are two mechanisms for money multipliers as discussed above: fractional reserve banking and collateralized banking (referred to as shadow banking). The ODM data above shows collateralized banking has collapsed by nearly half, down 42%. This is hardly surprising as private sector collateral has not grown (up 6%) and the Fed via QE has purchased and thereby withheld large portions of the public sector collateral that has grown (up 51%). In addition, the money multiplier graph above shows that the traditional fractional reserve banking relationship has also broken.

Referring to the earlier section on money creation above, the Fed has created money. That money is created as bank reserves. That is, they are on deposit with the Fed. It is an asset of the bank and the bank has the choice to exchange the cash (reserves) for another asset, such as a loan. If it does, then it needs to hold a fraction of the loan on reserve at the Fed. This is the source of the term fractional reserve banking. Reserves do not disappear; reserves are constant across the banking system but not for a particular bank. For a treatment as to why that is the case, read “Why Are Banks Holding So Many Excess Reserves” from the NY FRB. Reserves plus currency are the monetary base.

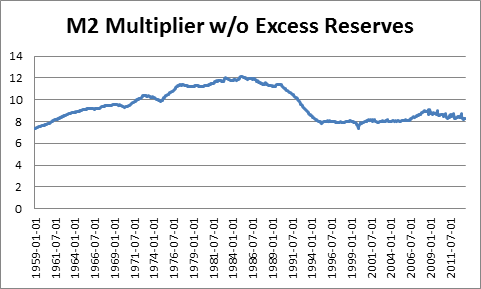

While the reserves do not disappear, they can be either required reserves backing “working” assets or excess reserves simply on deposit at the Fed. The required reserves represent money that has been multiplied. The excess reserves do not do any of the work of the economy. This chart re-draws the M2 money multiplier, but it reduces the monetary base by banks excess reserves:

Clearly, this looks far more normal. However, looking normal should not be confused with being correct. Nevertheless, the theory (that some large proportion of money is not being multiplied) and the data match. Regardless of the reason why money is being withheld as excess reserves, it is clear that so long as monetary base creation by the Fed is sitting as excess reserve balances, M2 can only grow linearly with additional money creation rather than geometrically.

Conclusion

This article has addressed monetary base creation, theoretical money multipliers and empirical money supply. At the very least, it is clear that for all of Bernanke’s effort with his helicopter, he has thus far been unable to create substantial effective money creation. Without that substantial effective money creation, money driven inflation cannot occur (a shortage of goods could still produce inflation). Until the transmission mechanism for the money multipliers kick in again, inflation will not be a problem.

The Low-Down on WTI

Paolo Santos on Seeking Alpha wrote an interesting piece titled “Weirdness Strikes the Crude Oil Market” and the current situation, on the surface, is weird. After all, according to the EIA, stockpiles of crude are essentially at the highest level in its time series. This is during a time that domestic production has dramatically increased and is expected to continue increasing. One would be forgiven for being surprised that WTI broke out of its range to higher prices. Front month WTI futures are around $103. The last time WTI traded $103 was May 2012 and that was before stockpiles went much higher than 350M barrels (they are currently close to 400M barrels). Here is a thesis to try to make sense of higher spot WTI prices amid supply.

Background

As background, the WTI-Brent spread that exploded to Brent’s favor reaching close to $25 has now collapsed below $5. Keep in mind that Brent is the inferior crude oil as it costs more to crack. Meaning, all things being equal, WTI should trade higher than Brent. All things, of course, were not equal.

Also, there was a tremendous amount of passively indexed commodity investing. Passive commodity investing is essentially always done as investment in futures and is based on three sources of return: spot price change, collateral return and roll yield. Spot price change is the change in price of the commodity itself and is what everyone is most familiar with in commodities investing. Passive investment is done using futures. One earns a collateral return on posted margin, which is usually a Treasury Bills. Most indices and funds, such as the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index (GSCI) and United States Oil ETF (USO) purchase front month futures and, near expiration, “roll” into the next month. That is, the fund sells the front month and buys the second month. If one is able to sell the front month at a higher price than the second month, then this earns a roll return. The opposite occurs if the second month is higher. When the front month is higher than the second, this is called backwardation and the reverse (2nd month higher than front month) contango. Indexed investors want backwardation to earn roll yield. As it turns out, the historical source of returns in commodities comes from the collateral and roll returns; spot price returns are volatile and average out over time (source: Expected Returns, Ilmanen).

The index and ETF investors became a very large part of the crude oil market. The impact was big enough that their futures expiration trading got its own name, the “Goldman Roll,” along with a Wikipedia page. The futures market has long since adjusted for the roll, but the point is that index investing has been a large part of the energy market for some time. That impact eventually hammered the crude oil futures market from backwardation to contango (ascribing causes in the markets can be a sketchy proposition but given the circumstances this looks like the most sensible conclusion). What is evident is that for index investors, their collateral margin was held to nearly 0% on TBills and their roll yield was now negative due to contango in the WTI market. It appears that when real yields popped from negative to positive (10 year TIP yields as proxy have move from about -.7% to .6% in 2 months – absolutely staggering), commodity investors threw in the towel and sold their underperforming funds. All three legs had negative expectations. Although I don’t have figures showing outflows from GSCI indexing, as proxy we can follow the path of USO, where outstanding shares have been on a clear, though erratic, trend down since Dec 2012. Since the beginning of 2013, shares outstanding have fallen from around 35M to 18.8M as last reported (source: Bloomberg).

The Crude Carry Trade

Here is a graph of the difference between the 2nd calendar WTI contract and the 1st (Bloomberg); green (positive) indicates contango and red (negative) backwardation.

Contango allows those with storage capability to buy spot crude oil to store in Cushing (the WTI delivery point) so that they could then sell the forward at a higher price earning a nice yield in the process. There is a cost to storing the oil and the rule of thumb is the cost is 45-50c per month. That coincides with the median value for the spread at 49c over the period. But the average value is 77c with a high of $8.19. One can see the volatility on the chart above. So long as things don’t look they are going to stay in backwardation, it pays to store oil and withhold it from the market. Most of the time (the median), you will break even. But on average, you can earn 27c to 32c per month due to occasional spikes. That works out to 3.6-4.3% returns in a world of ZIRP. That is far better than the passive index investor was doing and without the volatility of spot prices. In fact, it was the index investors who were assuming the volatility of the spot price and paying the carry traders to store the oil that they had purchased in the futures market.

Now WTI is in backwardation. Those in the crude carry trade need to consider the persistence of the backwardation. There has been significant withdrawal of passive investor index money. Just as passive investor demand forced crude oil into contango from backwardation, it stands to reason that flows the other way (the exit of the passive investor) would usher backwardation back. Given the evidence of investor preferences to exit passive indexing, it makes sense for the WTI carry traders to reduce their risk.

WTI-Brent Spread

The EIA released figures last week that pushed WTI higher due to a drawdown of stocks by 10M barrels. Look at those figures and note that the bulk of the drawdown is due to lower imports. Think for a moment and it makes perfect sense: traders had been diverting oil headed to other delivery points, e.g., Brent, to send to Cushing in order to satisfy end-user oil demand play the carry trade. Of course, the crude is still being produced somewhere and has to be delivered. Now that there is no carry to earn, it makes sense to send it to the Brent delivery point and make 5 extra bucks per barrel.

If all of that makes sense, then it stands to reason that your thinking would follow mine. And after going through this, I figured I could test the hypothesis by checking what the Brent term structure looked like over time. I expected to find that the WTI-Brent spread blow out coinciding with Brent moving into backwardation. If backwardated, Brent would no longer be a desirable place to store crude because there would be no carry trade. Here is the history of the Brent premium (Bloomberg):

And here is the same calendar spread graph (2nd – 1st ) but for Brent crude:

Note that in mid-to-late 2010 Brent moved from contango to backwardation and that was when the Brent-WTI spread began to expand. And it has stayed wide until now, when the WTI contango gave way to backwardation. Certainly it began with some fits and starts. Moving oil is not stock trading; it takes time and resources and then builds momentum. Presumably the trade gets very crowded in 2011 and becomes volatile. Nevertheless the data fits the theory. Interestingly, there were several articles in 2009 and early 2010 covering the carry trade in the Brent market.

Why then is crude staging a strong rally despite the fact that domestic US production is high and climbing plus stocks are near all-time highs? The hidden truth is that it actually is not. Brent is not making any 52 week highs and is about $1 higher than a month ago. Brent was about $120 in Feb 2013 and now is $107ish. As it turns out, that type of performance also holds for crude futures one year out. 12 Month WTI has not even traded higher than where it was in June, just a month ago. So what has happened is that 1) spot WTI is converging with Brent bringing it higher 2) there was an overall boost to the market from the drawdown and payroll figures and 3) there is general uneasiness due to news from Egypt.

Further evidence of the impact of both the carry trade and commodity index investors comes from discussions with a NY options trader. He noted that non-WTI domestic oils traded more in line with Brent than WTI. Another, a products options trader, noted that heating oil and gasoline traded closer with Brent which matches the data point that other grades of domestic oil that would be used for those products traded like the commodity (Brent), not the financial collateral (WTI). Those data points indicate that WTI is/was the aberration, not Brent. WTI, after all, is the futures market used by indexers and the market that offered the contango opportunity, not Brent and not Gulf Coast sour.

Conclusion

So the apparent weirdness that is in the crude oil market turns out to not be weird, but instead signals a shift in the crude oil marketplace. Crude and other commodities were used as collateral in financing transactions – essentially physical repo. Higher real rates, tighter money, passive investor withdrawal and backwardation have eliminated the financial motivation for withholding oil from the market. It stands to reason that WTI crude will again trade more like a commodity instead of a carry asset – at least so long as passive indexers are leaving the market.

Yield Trek: Into Darkness, Part 2

“Random chance seems to have operated in our favor” — Spock

“In plain, non-Vulcan English, we’ve been lucky” — McCoy

“I believe I said that, Doctor” — Spock

The data shows that there have been large inflows of cash to yield bearing equity strategies. That is not enough to get worried. What I’d like to see before shorting is 1) elevated prices & valuations, 2) an illusion of safety, 3) feedback loops, 4) diminishing ability to put cash to work and 5) a catalyst. Fortunately, we are able to see all of these things in this yield trade.

Valuation: danger ahead for REITs

I first look at the data for non-REIT companies. Above is a chart showing price-to-earnings (P/E) and price-to-book (P/B) data for 4 heavily weighted dividend sectors. Those sectors are: utilities, consumer discretionary, consumer staples and industrials. These are GICS sectors and the data is from Bloomberg. The utilities P/B ratio is quite high. Bluntly, P/E ratios look relatively normal. However, take a look at the next graph showing revenue, earnings per share (EPS) and debt per share. Note:

1) consumer discretionary revenues have not caught up to pre-2008 highs, but EPS is significantly higher

2) revenue and EPS are higher for consumer staples, but debt/share is growing and is double pre-2000 levels

3) despite languishing revenue and EPS, utilities debt/share are at all-time highs

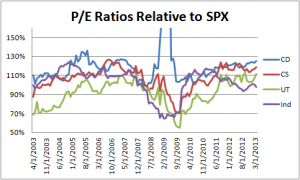

I’ve included another graph showing P/E ratios relative to the SPX P/E. Other than industrials, all of these four sectors look, at least, slightly rich. Utilities, in particular, looks very expensive compared to alternatives in the market. Overall, it looks clear that investors are overpaying for sectors considered to be dividend payers though not necessarily at nosebleed prices. Utilities valuations and debt burdens are showing definite warnings signs and should be avoided, or used as a candidate for the short side of sector pair trading.

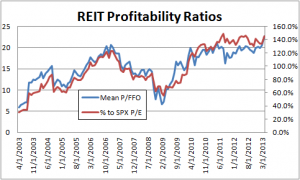

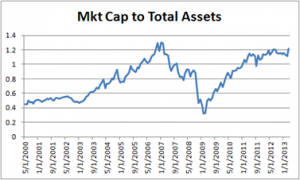

REITs are a different story. I’ve kept them separate because they use a different profitability metric, P/FFO. The data for this article is from Bloomberg and I was unable to get historical FFO data for the S&P REIT Index directly. Instead I took 5 major REITs (BXP, AVB, SPG, KIM, VNO) and aggregated the data. I took simple averages of their P/FFO ratios; not all series went back to 2003 but the latest started 2005. As can be easily seen, on both absolute and relative bases, REITs are at their highest profitability ratios in the last 10 years including during the real estate bubble.

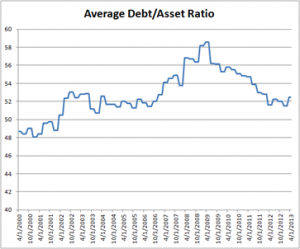

On the surface, it seems as though REITs have cleaned up their debt act a bit since 07/08. However, the reason for the peak of the debt/asset ratio in 2009 was due to the precipitous decline in the value of assets. Now with assets stabilized and even increasing, REITs have increased their debts so that the ratio is back to pre-crisis highs. In addition, the market is giving them an extremely generous market valuation for those assets. Market capitalization, for at least those major 5 REITs, is right back to pre-crisis, i.e., bubble level, highs. REITs are squarely in the danger zone based on valuation.

Illusion of Safety

With the exception of high yield bonds and, possibly, MLPs, dividend and low volatility strategies are touted as being safe (for example, here or here). But the safety that is being offered is measured using the rear-view mirror. Safety is being judged based on past performance – which we know is not a guarantee of future results. Measuring risk based on historical asset movements has three major flaws. The first is that it is measuring movement, not risk. For example, standard deviation does not differentiate between assets bouncing around and an earnings release that qualitatively changes a company outlook. Second, it does not account for asymmetric risk. Option positions are one type of asymmetric risk; buying an asset very cheaply or paying too high a price is another. Third, it creates feedback loops when large amounts of money move based on the same criteria. Low volatility invites larger asset purchases, particularly with leverage. This decreases realized volatility as prices move up which again invites larger purchases. Once inflows inevitably stop, volatility increases, causing risk reduction or margin calls as exposures must be managed based on newly assessed risk outlooks.

Low-volatility investing works by measuring prior period asset movement, much as Value-at-Risk (VaR) does. SPLV, the largest low volatility ETF, bases its holdings on realized volatility over the prior 12 months and rebalances quarterly. The nice thing about low volatility asset management is that it is based on solid empirical data. That’s good except for the part about how the data that was used for the studies did not count on large amounts of money following the same strategy. SPLV does not count on anything else other than qualifying as the 100 stocks out of the SPX with the lowest realized volatility. These assets tend to look like traditional dividend players – and heavy on REITs (10% for SPLV, less for others). If these holdings begin to get volatile, they will be forced to evict them from the portfolio which will then contribute to greater volatility.

Feedback Loops & Diminishing Ability to Buy More

In addition to the volatility based feedback discussed in the section above, there are other feedback loops at play:

1) Margin debt. Discussed here, note that the most recent release which was subsequent to that post, showed margin debt climbing to an all-time high.

2) High levels of bond funds holding equities. Discussed here.

3) Risk parity and similar strategies. Discussed in part 1.

4) Abenomics leads to Yen devaluation and Japanese “exporting” deflation. here and here. With Yen depreciation at least temporarily slowed, expect Japanese money to REITs to slow or stop.

5) One of the most interesting feedback loops also comes from Japan, where they, too are searching for high yield. In the Heard on the Street column from April 15, 2013, it was reported that Japanese investors have been searching for yield in vehicles that invest in US REITs. The key part is that they pay out unrealized (not a typo, unrealized) capital gains on the way up as dividends. That is amazing. One can only imagine the debacle if US REITs stop climbing. Oh yeah, and they are large holders of these stocks, too. According to the article, they own 8.6% of SPG and 10.1% of VNO. For those of you that remember chemistry class, this reminds me of a super-saturated, barely stable solution ready to blow (think Diet Coke & Mentos).

Catalyst

This is the toughest part about investing. Even if one presumes enough to believe that one has the correct analysis, it is no good to be too early (e.g., Abnormal Returns from 2011). What might be a catalyst could turn out to be a bump in the road. That said, I believe that we have seen the catalysts to shake things up. First, FX market volatility has picked up. After hitting multi-year lows at the end of 2012, the JP Morgan global FX volatility index has rebounded to 2010-2011 levels. This is due to Yen weakening. Second, that volatility has spilled over into commodity markets, most noticeably gold & silver. I consider this to be a canary in the coal mine. Finally, the potential for the Fed to slow or stop purchases in the mortgage markets will have a huge impact on volatility and asset prices. Fixed income prices have begun to re-price the possibility of this and it has sent 10 year note yields to their highest level since beginning of 2012 in just a few sessions. Recall too that the Fed effectively sells volatility by buying mortgage paper (there is an embedded pre-payment option).

Conclusion

All well and good, but what is the elevator speech? Too much money, most seemingly leveraged money, is chasing the latest investment craze – yield in dividend stocks. The most distended market is for REITs which looks particularly expensive by benchmark measures. Further, the investor class in REITs is a large set of “weak hands.” That is, they are investors who will need to exit (due to margin calls or structural investment guidelines) at the first sign of trouble and they are too large a proportion of owners to make the exit orderly. While other areas of dividend investing may look rich, REITs are where the focus should be for short ideas. The time is soon approaching when this will occur – already some volatility has been creeping into REIT shares and ETFs. It is hard to imagine that continued inflows will recur. And once the support for an overvalued asset stops, the decline can begin.

The Fed, the Shadow Banking System and the Law of Unintended Consequences

Andy Kessler writes on the opinion page of the Wall Street Journal about Fed policy, collateral and the shadow banking system. This is definitely an inside baseball type story. But this is a case where the detail work makes a big difference to the big picture. The quick version is that banks use high quality collateral, i.e., government and mortgage debt, to create credit. They do this by re-hypothecation in the repo (repurchase agreement market). His point is to criticize Fed policy, presumably with the idea of “correcting” it. If he is correct, and I think that he is at least partially correct, then the immediate implications are far more interesting than a critique of Fed policy.

First, here is a bit of background. A repo is nothing more than a collateralized loan. For example, I purchase a 10 year note and want to finance it. The cheapest way to do so is in the repo market where I post the note as collateral. It is called a repurchase agreement because rather than create a loan, I simultaneously sell the note to the bank and negotiate a forward “repurchase” of it. Voila. The bank is happy because it has a liquid asset backing its loan (not like a house) and it has a very good handle on its value. Plus it demands the loan be over-collateralized. I’m happy because I’m getting an extremely good rate due to the safety of the loan.

The bank now has a 10 year note on its balance sheet. Banks don’t like to waste balance sheet; they get measured on their efficient use of it. So the bank does a repo with the 10 year note from me. Now they have the cash, minus the overcollateralization amounts. Bam! Money created. That process is called re-hypothecation (simply because the original loan is called hypothecation. Fortunately, the next transaction is still called re-hypothecation and not re-re-hypothecation.).

Before anyone lays down judgment on how this shows how banks shouldn’t be able to create out of control fiat credit, please realize I’m reporting what happens. I’m not interested right now in whether it is a good idea or not.

The first question is whether he is correct. There is no doubt that the Fed is buying truckloads of bonds. This article from Bloomberg in December estimates that the Fed will be the buyer of 90% of new dollar denominated assets. The Fed focuses on the highest quality (most credit worthy and liquid) issues, i.e., government and mortgage debt. So there clearly is a critically small amount of issuance available. Further, this IMF paper documents the re-hypothecation in the banking system.

To review: 1) The Fed’s QE policy is reducing the amount of usable collateral for hypothecation, 2) this collateral is critical for the “shadow” banking sector, and 3) the “shadow” banking sector is a larger credit creation mechanism than the Fed’s QE. The Fed has stated that its goal is to keep QE going until economic growth gains momentum. Based on this analysis, the clear conclusion is that right as the Fed wants to unwind QE to take the pedal off of the gas, collateral will become available and the credit creation from the shadow banking system will kick in. The implication is that the Fed will have trouble keeping credit creation under control and that inflation will become a real risk.

Yield Trek: Into Darkness Part 1

“Mr. Spock, the women on your planet are logical. That’s the only planet in the galaxy that can make that claim.” – Captain Kirk

This post has taken far longer for me to put together than I had anticipated. I spent quite a bit of time putting together the data and moving down paths that didn’t work. It is also taking more text & space than I had anticipated. Therefore I am splitting this into multiple posts. This first post covers the explosion of assets in yield bearing equities. One last editorial note, substitute “investors” for women in the quote above.

In at least on respect, FED policy is working: QE via its bond buying program is forcing investors up the risk curve. And that is making for an unintentionally very over-crowded trade. This is because multiple trends are coming together into the same or similar assets due to investors’ search for yield and safety. It is the natural reaction investors have to getting burned twice before reaching for capital gains: first in 2000 with dotcoms and in 2008 in real estate. Rather than seek capital gains, they are trying to play it safe by being content to collect dividends. But investors are paying high prices for small cash flows and the quest for yield is playing out in bulk. If this plays out as another crash as I expect it will, the irony will be that investors were trying to be conservative.

Here are some of the trends:

– Dividend stocks

– REITs

– MLPs

– Preferred stocks

– Low-volatility investing

– Risk parity investing

– Yen depreciation

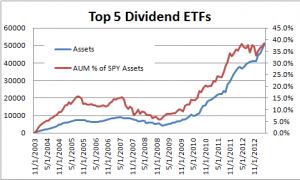

It’s easy to see how a quest for yield leads investors to these first four sectors of the stock market. Even bond investors seem to be getting into the act. There is an enormous amount of money chasing these sectors and the data to support that follows. First, consider dividend paying stocks. I’ve put together data on fund assets under management (AUM) for the top 5 dividend ETFs. These account for the vast majority of dividend ETF assets. Of course, mutual fund assets are larger, but this data should capture the money flow trends. The chart shows the hockey stick growth of assets both on an absolute basis and compared to SPY assets. When looking at the percentage figures, keep in mind that SPY assets have also grown aggressively recently, having increased by over 28% in the past year and most of that, 21%, in the past 6 months. That’s not bad for a fund that a year ago had $100B.

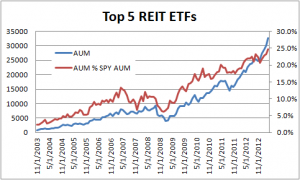

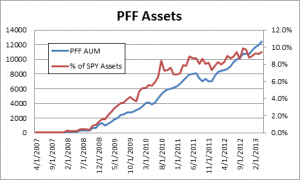

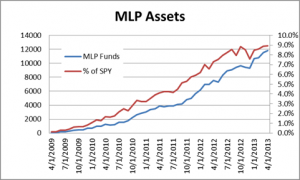

Overall, the top 5 dividend ETF assets has exploded in the past two years to over $50B (incidentally higher than that managed by GLD) – managing 4X the assets as at the end of 2010. Chart data from Bloomberg. REIT ETFs have doubled in size since the end of 2010 from a sizable asset base of $14B. PFF accounts for so much of the preferred ETF market that it is the only fund that I listed. It, too, has more than quadrupled its assets since the end of 2010. MLP assets have grown very quickly to become nearly $12B.

Clearly, an incredible amount of money has been rushed into these yield related stocks in the past two years – just in ETFs alone. But it gets more interesting. Although low volatility investing as a concept has been around for some time, it has recently become very popular. Consider that SPLV, the leading low volatility(LV) ETF, launched in May 2011 and already with over $5B in assets. SPLV’s largest competitor, USMV, was launched October 2011 and now has $3.5B. The Top 5 low volatility ETFs combined are managing $12.6B which is about 9.5% of the size of SPY. These funds have been in such demand that their assets have more than doubled this year (all 5 months of it).

Certainly there is significantly more money than this in the mutual fund complex and under non-categorized active management following low-volatility strategies. But the kicker here is that these low volatility funds look a lot like their dividend ETF competitors. First, they are very heavily weighted in the consumer (combined consumer staples & discretionary) with weightings around 20%, very comparable with dividend funds that have slightly higher concentrations in the mid-20%s and also the SPX. They have higher than SPX weightings in utilities, with dividend ETFs having a typically very heavy 10-30% (with Vanguard having 1%) and LV ETFs having between 9-30% weightings, compared with 3.3% for the SPX. LV ETFs are also very heavily weighted in real estate (including REITs). SPLV accounts for nearly half of LV ETF assets and holds 10% in real estate and the next two holding 7% and 2% respectively vs. 2% for SPX.

Another new, but prevalent trend in investing is called risk parity investing. The idea is, roughly speaking, to allocate assets in a portfolio such that each asset class’s variability (risk) is equal. For example, bonds typically have lower volatility than equities, thus the bond allocation would be levered up until the new allocation had a perceived volatility equivalent to the equity component. Each manager handles this slightly differently. But they might lever up on low volatility equity sectors to match, say, technology shares or the market as a whole. Frankly, it is beyond my capabilities at this time to provide a reasonable metric on how much money is involved in risk parity. There is an interesting discussion about it here and an article here. My feeling is that there are large amounts of assets put to work in this way, but I prefer data to feelings. Input would be very welcome.

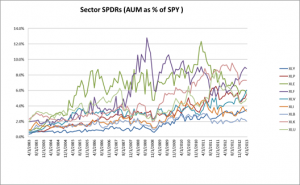

To provide a more complete picture, take a look at this next chart that shows Sector SPDR assets as a percentage of SPY assets. This shows that prior data was not documenting a secular decline in SPY assets relative to other ETFs. One can see that on a relative basis that some sectors have gathered assets and other lost. In particular, it is worth noting that the utilities sector (XLU) has seen a recent and dramatic drop in assets. This is a bit odd since utilities are the poster boy for dividend stocks. It might mean that investors wanted to diversify into a number of dividend payers, presumably for risk reduction. However, recall that utilities represent a significant part of dividend ETF portfolios and the dividend ETFs are far larger than XLU so that even that fraction (as high as 30%) can easily offset (relative) outflows from XLU.

How Much is Too Much?

“The crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought, and that’s sort of exactly the Mexican story. It took forever and then it took a night.”

– Rudiger Dornbusch

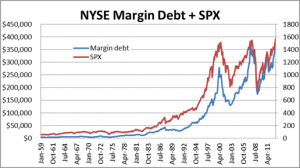

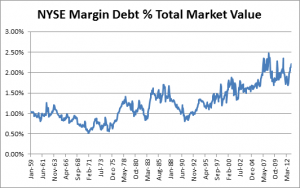

There have been some articles circulating about NYSE margin debt, e.g., here, and I think it is worthwhile to take a look at this. One response to these words of caution was that margin debt as a percentage of stock market capitalization is within a normal range. For myself, I want to put this in context. Here is some data. Note how the drop in margin debt and SPX in both 1987 and 1998 barely register. I wasn’t in the business for 87, but I can assure that the LTCM selloff in 1998 was significant in many ways.

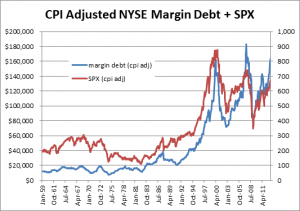

There is a pretty nice correlation of peaks (yes, that’s the technical term) between margin debt highs and SPX highs, followed by steep drop-offs. The conclusion is clear: get short when margin debt peaks. Which leads to the equally clear problem: one can’t tell the peak until afterwards. At least for this data, we can feel comfortable about correlation meeting causation. Leveraged buyers are weak hands because their choice is limited by the margin clerk. Once prices start falling, margin selling leads to further margin selling. To address some concerns about how much margin debt is too much, I’ve created two additional charts that re-slice the numbers a bit.

I think that the CPI adjusted margin debt adds some information as it shows that “real” margin debt is about the same as in 2000 rather than being much higher. On the other hand, looking at debt as a percentage of total market capitalization dilutes the information. It shows how the market has become more debt driven than in decades past, but it doesn’t add a red signal at any point. No danger zone for ’87, ’98, ’00, ‘07/08.

What is my conclusion here? Be afraid. Be very afraid. But these things tend to take longer to play out than one expects. In fact, the Rudiger Dornbusch quote from above captures it perfectly. Trades like this get called the widowmaker for a reason. There is evidence of weak hands playing a dangerous game. It would be great if we could find a crowded trade in overpriced assets. Yeah, and then cheap, asymmetric bets to make.

There is more to this story, but it will have to wait for the next post.